The Perch Culture

The Perch Culture

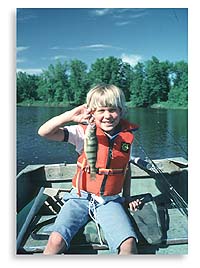

Sunlight floods childhood memories of summer on the St. Lawrence River like bright lights in a boundless arena. Smoothly moving water seemed to rise up into the sky on an endless horizon. Shafts of sunlight funneled into greenish depths, appearing to rotate as we passed over the surface. I often wondered what strange fish or monsters lay in the darkness below. Dozens of skinny shiners rested patiently in a deep bucket, their big heads spaced randomly like a handful of wooden matches scattered on a tabletop, but with one more dimension spreading them down through the water. It was endlessly fascinating to chase them in circles and cup the flickering tinsel strips of silvery life in my hands. In the early days, the family spent summers on the river. Dad directed operations from the back of the boat, while mother, seated in the front, divided her attention between the kids, the newest baby nestled in a basket under the bow, and the bamboo pole she used to swing double-headers of thick yellow perch into the boat. My brothers, sisters, and I were generally scattered in between, talking incessantly, swinging long poles in and out, and clattering over the minnow buckets to pick up flopping perch. The finest moments I recall were watching the shiners spiral down on a perch rig, waiting a poignant moment for the first heavy thump of a jumbo, then the second, and snapping upwards, feeling the weight strain and vibrate the pole as the fish tugged in circles. Swinging 2 pounds (.9 kg) of struggling perch into a wooden boat is a challenge for a youngster with a short reach. Old South Bend reels were only used for storing heavy, black Dacron line. Fish were brought in by retrieving line through the guides with the left hand, while raising the pole with the right. In deeper water, with really big perch, we would often use our teeth to hold tension on the line as we reached out to pull dangling fish on board. Sometimes perch on the lower hook would thump against the gunwale and plop into the water. This was always funny, unless it happened to me.  Perch fishing was more than a pastime, it was a part of family life that provided the best memories together, and valuable nourishment to a growing family of nine. I remember long evenings well after bedtime, watching my father patiently work through mounds of dark-golden perch on the kitchen table. Hand-crafted fillets were carved from each fish with precise cuts, using the little pocket knife he carried everywhere. Perch and the river, the family and my youth all seemed to blend together in a meaningful way. The places we fished and the things we did together often depended on where the perch were and what they were doing. In some ways, our lifestyle followed the natural rhythms of this prolific fish, through traditions that were probably not unfamiliar to our tribal ancestors. Perch fishing was more than a pastime, it was a part of family life that provided the best memories together, and valuable nourishment to a growing family of nine. I remember long evenings well after bedtime, watching my father patiently work through mounds of dark-golden perch on the kitchen table. Hand-crafted fillets were carved from each fish with precise cuts, using the little pocket knife he carried everywhere. Perch and the river, the family and my youth all seemed to blend together in a meaningful way. The places we fished and the things we did together often depended on where the perch were and what they were doing. In some ways, our lifestyle followed the natural rhythms of this prolific fish, through traditions that were probably not unfamiliar to our tribal ancestors. The spring spawning run would find us working up the fast water to a place called the "Second Falls," or farther afield in Lake St. Francis, off the mouth of a creek or up one of the inflowing rivers. Big schools of jumbos patrolled the shorelines in these places, sleek males chasing heavy, roe-laden females as they spread their eggs over weeds, rocks, and brush in shallow water. Often, the boat's floor-boards would become slick with milt and eggs from flopping fish. Having young, inquisitive minds at the time, avoiding the most obvious questions was difficult. Without heavy weedgrowth to focus schools and food sources, perch scattered widely in early summer. By mid-summer, they were schooling again, feeding on shrimp and small snails clinging to the undulating vegetation that defined reefs, holes, and current edges. We spent days anchored on current edges, fishing weed pockets, or drifting on bright afternoons over endless flats, watching schools of perch and sun-baked bronze-backed smallmouth bass cruising across bright spots between gently swaying weeds. As summer slipped away, the first fish racing to the bait in these holes were aggressive pairs of pot-bellied bass. Occasionally, double-headers would break the surface in different directions. Monstrous walleye, eager to grab a nightcrawler trailing on the bottom hook, also hung out under cover near fast water. I still have memories of Dad describing walleye with "eyes as big as saucers" rising from the darkness under the mysterious weed edges. Winter was a magical time in back-bays and quiet stretches of the river. First ice found perch pouncing on shiners offered on tip-ups or attached to a jigging spoon. As winter progressed, perch jigging became an art form, with just the right touch needed to coax reluctant fish. The bite was focused in the morning and evening, with moon phase playing a prominent role in determining fish activity levels. The glory days arrived in late March or April, as the strengthening sun turned the upper layer of ice into slush and Canada geese barked from open stretches along channels.  Pre-spawning jumbos fed voraciously in back-waters and at the mouths of inflowing streams. Furious action, sunburn, and perch averaging well over a pound apiece were the hallmarks of those delicious spring days with my father and friends. Pre-spawning jumbos fed voraciously in back-waters and at the mouths of inflowing streams. Furious action, sunburn, and perch averaging well over a pound apiece were the hallmarks of those delicious spring days with my father and friends. Webster's Dictionary defines culture as tillage or cultivation; mental training and development; refinement; civilization. Tradition is described as belief; custom; narrative, transmitted by word of mouth from age to age. Perch culture and traditions fit these definitions, yet those among us who can identify with this lifestyle have not recognized its cultural aspects and taken the steps to document and preserve it. People seem to rely on outsiders to document their culture. Perch culture is part of a modern hunting and gathering lifestyle often imposed on and integrated with an advancing technological society. It is an important adaptation, a bridge between a subsistence and a technological world. The culture strengthens the family unit, while training and developing children in life skills, knowledge and an enduring link with the natural world. The perch culture is transferred from generation to generation through family traditions, built on the stories, knowledge, skills, and activities related to the fishery. This might be symbolized in some cultures through art, literature, and music, but nothing so compelling seems to be forthcoming for the yellow perch. This bread-and-butter fish remains an inconspicuous foundation of life on the river. Although perch can be caught throughout the year, traditional fishing seasons and angling and handling techniques differ from province to province and even from one community to the next. Taken together, these traditions form a rich and diverse culture based on perch fishing across the country. The St. Lawrence River is the backbone of perch culture in my area, but Lake St. Francis, sharing a border with Quebec, is the cultural epicentre. Here, hot dog and patate frite stands offer perch rolls in both official languages, and secret sauces are jealously guarded. Shoreline restaurants offer perch platters, and locals say good perch are eight to the pound. The vast bays and open water of this productive ecosystem are ideal perch habitat, and the fish have supported a unique lifestyle for many of the shoreline inhabitants over the years.  Ed "Buster" Levy, a mere pup of 81 years, has spent more than 50 of them fishing for perch on the lake. Robin Casgrain, 50, a long-time fishing friend from Cornwall, also was raised along the shore of the big lake and was fortunate to be tutored in the ways of fish and wildlife by some of the best guides. Knowledge and stories flow easily from these men, but it is their unspoken attachment to this waterbody that draws one into the conversation and into their lives. Through their stories, these men convey a special understanding and almost spiritual reverence for the river. Invariably, the conversation meanders like the great stream, flowing through colourful tales of muskie, walleye, guides, and ducks, but it always returns to perch. This fish is the centre and measure of the lake and of the people who surround it. Ed "Buster" Levy, a mere pup of 81 years, has spent more than 50 of them fishing for perch on the lake. Robin Casgrain, 50, a long-time fishing friend from Cornwall, also was raised along the shore of the big lake and was fortunate to be tutored in the ways of fish and wildlife by some of the best guides. Knowledge and stories flow easily from these men, but it is their unspoken attachment to this waterbody that draws one into the conversation and into their lives. Through their stories, these men convey a special understanding and almost spiritual reverence for the river. Invariably, the conversation meanders like the great stream, flowing through colourful tales of muskie, walleye, guides, and ducks, but it always returns to perch. This fish is the centre and measure of the lake and of the people who surround it. I walk the shoreline of the lake in spring, with a white plastic bucket and a bobber rig for lobbing shiners out to crappie that sometimes frequent the back-waters. Perch fishing is now closed until after they spawn. I watch the bobber drift and think about changes I've seen in the perch, the lake, and the culture over the past 50 years. The perch are fairly abundant, but very small. They look like they were made by the same cookie cutter, like the tiny walleye I'd seen in Manitoba's big lakes, over-exploited by tremendous commercial-fishing pressure. The fish simply don't have a chance to grow larger. The perch culture is also changing. I see fewer families out fishing, but an explosion of men in boats, jockeying competitively in an unlimited-entry, largely unmonitored commercial angling fishery. Lake St. Francis remains the only location in Ontario where angler-caught perch can be legally sold. The perch are sold whole, so the long process of preparing them for market is no longer a hindrance to exploitation. Many of the new commercial anglers do not know how to clean fish. With dwindling employment opportunities in the area, politicians will be slow to curtail netting and commercial angling. It seems only a matter of time before the fishery bottoms out. Restaurants have been running short of perch, and fishermen have been ranging far afield catching fish in lakes around Ottawa and beyond for sale at the Bainsville fish market. The Ministry of Natural Resources is aware that the size of perch has declined, but many area people support the tradition of selling them. There is also a local desire to return to a quality fishery, with decent numbers of jumbo perch. This seems impossible, unless the community is willing to take steps to allow more perch to live longer and grow. Current mortality rates might be as high as 80 per cent, which means that only two out of 10 perch survive from one year to the next. Most are removed by fishing. The spring closure is a step in the right direction, but it might not be enough in the face of growing participation in the commercial angling fishery. I also wonder if this competitive fishery fosters the behaviour and ethics needed to ensure a future for sportfishing. When it becomes a business, some new entrepreneurs might only see the money. Knowledge and respect for fishing traditions, perch, and the river take time, commitment, and training to cultivate in people, but they are the building blocks of conservation and vital to the survival of the perch culture. Elsewhere, it's hanging on, but faces challenges from a technology-driven society that is rapidly moving farther from its roots in the natural world. Technology, they say, is a way of arranging life so people don't have to live it, so we hunt for our meat at supermarkets and get our fish from a can. A generation of technological lifestyle has contributed to a spiritual disconnection with the natural world. New organizations that do not recognize a valid role for humans in natural ecosystems are springing up against fishing and hunting.  Buster Levy says fishing is a gift, one he would like to give to children everywhere. In his own way, he has accomplished a little of that by preparing special fishing rigs and handing them out to kids. The perch culture needs rejuvenation at the centre and new ideas that can only come from those who understand it and wish to provide its gifts to the next generation. Perhaps perch festivals, such as the one held in Orillia where families are encouraged to attend and children are taught how to catch and clean fish, are one way of fostering stronger communities. Getting people like Buster Levy together with kids to talk about perch fishing and help them wet a line or two is certainly another. Buster Levy says fishing is a gift, one he would like to give to children everywhere. In his own way, he has accomplished a little of that by preparing special fishing rigs and handing them out to kids. The perch culture needs rejuvenation at the centre and new ideas that can only come from those who understand it and wish to provide its gifts to the next generation. Perhaps perch festivals, such as the one held in Orillia where families are encouraged to attend and children are taught how to catch and clean fish, are one way of fostering stronger communities. Getting people like Buster Levy together with kids to talk about perch fishing and help them wet a line or two is certainly another. The perch culture has no temples, monuments, or sacred scrolls to entice learned societies to record its passing or to ponder its depths. It is a simple culture, based on a lifestyle that cultivates some of the best qualities in people and strengthens their ties to the environment. Its gifts are knowledge, appreciation, and a way of valuing nature, family life, and outdoor traditions. Later in life, a need for spiritual re-creation draws some people back to the river in their quest for perch. These are gifts borrowed from our children that no money can ever replace. It's a culture with traditions worth saving. This article is written with permission by Fish Ontario. Visit their website, http://www.fishontario.com, for more Ontario fishing information.

Fish Ontario

|