Fly Fishing with Doug Macnair: All About Lines: Part 2©

Fly Fishing with Doug Macnair: All About Lines: Part 2©

From his manuscript, Fly Fishing for the Rest of Us

Now that you have an understanding of the AFTMA fly line standards, it’s time to take a look at the types of lines and, importantly, what wondrous things the manufacturers can do when they tinker with the weight distribution in the line’s first thirty feet.

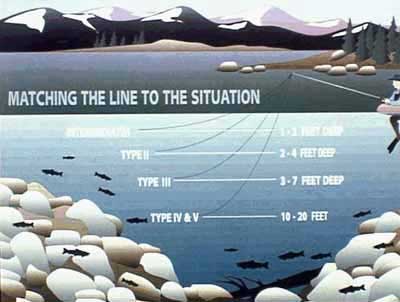

There are two types of fly lines -- those that float and those that sink. Of the two, I find the sinkers to be a remarkable lot. While they all sink, they do it in different ways: some barely sink, others sink very quickly and very deep, still others sink not so quickly and not so deep. There are even those that sink only at the tip, the rest of the line remaining afloat or slightly below the surface. This later group constitutes the relatively new sink-tip lines, a blend of both worlds.

The rationale behind this potpourri of lines is really quite simple. Reasonably speaking, if your fly is at one depth and the fish is at another, you are not going to catch fish. Profound? You bet! You must be able to fish the entire water column from top to bottom to consistently catch fish. Consequently, the fly fisher needs multiple fly lines if he or she is to become proficient practicing the gentle art.

Remember when I earlier suggested that the fly line is the most important part the fly fishing? Simply stated, it’s the fly line that makes 70% of the cast -- credit the rod with the remainder. Now comes the second reason: it's the fly line that takes the fly to the right level in the water column, not the rod. If you cannot put your fly where the fish are holding, it doesn’t matter how much the rod cost or how fancy the reel. While this makes perfectly good sense to me, I am always amazed at the number of fly fishers who arm themselves only with floating lines. Admittedly, the floaters are easy to cast. But, if I had to guess, fish are either at or near the surface only about 10% of the time. Thus, a fly fisher who fishes only the surface defies the odds of catching fish. Are you one of those losers?

Of course, if you only plan to fish little streams and small creeks, a floater might prove to be all you will ever need. Certainly, making the leader sink is no big deal and that will get the fly down two roughly three feet. But if you plan to fish a pond, lake, big river, or the ocean blue, you will need a few sinkers and sink-tips, too. The truth is the manufacturers have provided us a chance to choose a fly line for "just the right occasion." Unfortunately, they cannot choose for us. It’s up to you and me to take advantage of what it is each line can and cannot do. As an example, the intermediate is my line of choice for a bunch of situations. For those who may not know, the intermediate is the slowest of the sinkers. In fact, its sink-depth is measured in inches. In a situation such as fishing the saltwater flats the intermediate casts better in a breeze and, once cast, rides below the surface and the probable wave action or floating weed.

So why do so many fly fishers limit themselves to floating lines? It’s simple. They cannot handle a sinking line. If you are new to the game, give this thought the once-over. Regardless of the rod, you cannot lift a fly line into the backcast if it is submerged beneath the surface. To lift into the backcast, the line must be riding on top of the surface film. Thus, to cast any of the sinkers - including the sink-tips - the fly fisher must first execute a roll cast to surface the submerged line before the standard backcast can be initiated. Timing is important because the line must be lifted into the air before it sinks back into the surface film.

The funny thing about the roll cast is that it can only be practiced on the water. It is the water’s drag against the movement of the line that loads the rod thereby enabling the cast. No water - no drag, no loading - no cast. Many fly fishers never practice the roll cast because the only time they get close to water is when they go fishing or take a bath. Most bathtubs are far to short to use as a substitute for a real body water.

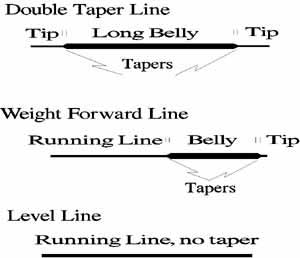

It seems to me that it is very difficult to become proficient without practicing, thereby acquiring the requisite roll casting skills. Of course, many fly fishers never practice casting at all. One other point - the most popular lines, those constructed with a weight-forward taper, do not roll cast nearly as well as the double-taper, a line some consider antiquated. Nothing, however, could be further from the truth.

It seems to me that it is very difficult to become proficient without practicing, thereby acquiring the requisite roll casting skills. Of course, many fly fishers never practice casting at all. One other point - the most popular lines, those constructed with a weight-forward taper, do not roll cast nearly as well as the double-taper, a line some consider antiquated. Nothing, however, could be further from the truth.

Fly Line Construction. While the formulas, ingredients, and bonding agents are proprietary to the manufacturer, it’s fair to say that the fly line consists of a core, a coating, and a taper.

(1) The Core: The core’s contribution to the fly line is strength, stretch and, somewhat to stiffness. We touched on stiffness and stretch earlier when discussing the extremes such as lines built for tropic waters as opposed to those designed for more temperate zones. A line built to withstand high heat and saltwater does not fare well when meeting cool conditions. The problem of line set stemming from the core’s stiffness will drive you wild. Reverse the situation and things are no better. The line for cooler zones will drive you wild in the tropics, unless you have a fetish for casting cooked spaghetti. Strength, on the other hand, is something the typical fly fisher need not be concerned with. Suffice it to say that any fly line is built to be much stronger than the tippet, always the weakest link in the fly fishing system. I deliberately broke a 5-weight floater and according to my imperfect scale, the break occurred at about 30-pounds, dead weight.

(2) The Coating: The coating makes its major contribution by giving the line weight, durability and density. It’s the density of the line that primarily determines whether or not the line floats or sinks. So the ingredients of the coating take on great importance, especially when you consider the AFTMA weight standards earlier discussed. The standards apply regardless of whether the line floats or sinks. Specific coatings are carefully guarded secrets; however, most are derived from some form of plastic I call PVC. Whether or not it is truly a PVC isn’t as important as remembering the vulnerability of some plastics to chemicals and lubricants. Fly lines can be easily damaged or ruined if they come in contact with insect repellents, such as Off, and something like WD-40. Since I regard the fly line as the most important part of the system, I buy the best available. A good fly line will last many years given a little tender love and kindness along with the frugal pocketbook of a Scot.

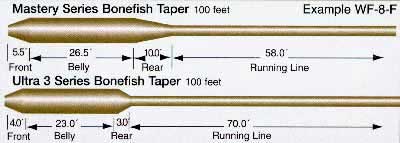

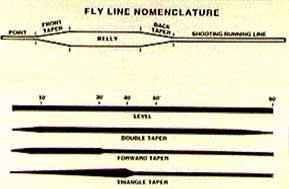

(3) The Taper: The line’s taper, in relation to the specific coating and core, pretty well determines the casting performance. Remember that the manufacturer has the first thirty feet of line to tinker with in how the weight is distributed. Beyond the first thirty fee, manufacturers can add or delete weight as they see fit because anything beyond thirty feet is outside of the parameters of the AFTMA standards. Note the differences in these in these two Scientific Anglers weight-forward lines.

(a) Weight-Forward Line: The head, or more appropriately the head section, includes both the front and rear taper and the belly of the line -- that part of the line with the greatest diameter. The belly carries most of the line’s casting energy. Simply stated, the weight is forward. Typically, a long front taper enables a more delicate presentation while a short front taper provides for a more powerful delivery. In the case of a weight-forward line, the thin part behind the rear taper is called the running line. Because it is relatively thin and lightweight, the running line follows the head exerting little drag as it rattles through the guides. The ability to gain a greater distance during the cast explains this line’s popularity. Importantly, the head can take a variety of configurations. The Triangle Taper, for example, begins with a rather thin tip and progressively increases in diameter for about fifty feet. The fact that the head extends beyond the first thirty feet matters not at all. The line weight fully complies with the AFTMA standard in the first thirty feet. It’s this sort of manufacturing flexibility in distributing weight, while staying within the parameters of a standard, that has contributed to making what it is today -- outstanding!

(b) Double Taper Line: If you have a constant need to roll cast because of heavy brush or tree and are satisfied with less than a new world’s record for casting distance, give the double-taper a try. The double-taper will out roll cast and out perform a true weight-forward line with its limited roll-casting range of 25 to 35-feet. The double-taper will enable you to reach out and touch something, hopefully a fish. It is the long belly sandwiched between the front and rear taper that makes this a reality. In the roll cast, energy must be transmitted by the line to itself from the rear to the front -- to that part of the line still in the water. In contrast, to the double-taper’s construction, the weight-forward’s light thin running line does a poor job powering the head into the necessary turn over to return it to the surface. As you might guess, the Triangle Taper roll casts nicely to at least fifty feet simply because Lee Wulff thought a heavier line should always be turning over a lighter line.

(b) Double Taper Line: If you have a constant need to roll cast because of heavy brush or tree and are satisfied with less than a new world’s record for casting distance, give the double-taper a try. The double-taper will out roll cast and out perform a true weight-forward line with its limited roll-casting range of 25 to 35-feet. The double-taper will enable you to reach out and touch something, hopefully a fish. It is the long belly sandwiched between the front and rear taper that makes this a reality. In the roll cast, energy must be transmitted by the line to itself from the rear to the front -- to that part of the line still in the water. In contrast, to the double-taper’s construction, the weight-forward’s light thin running line does a poor job powering the head into the necessary turn over to return it to the surface. As you might guess, the Triangle Taper roll casts nicely to at least fifty feet simply because Lee Wulff thought a heavier line should always be turning over a lighter line.

Are there other virtues to a double-taper line? Certainly! It carries the reputation of making consistently gentle presentations in the hands of a good caster. And when one end of the line begins to show a little wear, switch ends and start over with an almost new line. The tapers at both ends are exactly alike. Finally, if you ever get involved in making your own shooting tapers, there is no better choice than to begin with a double-taper line. It’s one of the few times in fly fishing where you are guaranteed two for the price of one. We will examine the shooting tapers later. One final thought: depending on the weight and the skills of the caster, I doubt there is much more than ten to twelve feet difference between the long casts of a typical weight-forward and a matching double-taper line. Since more fish are caught within thirty feet of the fly fisher, do not get hyped by the hyperbole of some writers.

"Well, the time has come," as the Walrus said, "for me to quit and get ready for bed." The dream of Hermann Smuck's huge trout looms large in front of my drooping eyelids. Yes, the call of the wild fish beckons. For now, this must suffice. Next time we will uncover the meaning of the secret codes of the fly lines, using our Lone Ranger Decoder Ring, list a few places where you write for other source materials on lines, and discuss the shooting tapers, something no fly fisher should ever overlook. Until then, God Bless.

© Copyright: Douglas G. Macnair, 1997-2000.

|