Our Outdoors: The Norway Chronicles

Our Outdoors: The Norway Chronicles

By Nick Simonson

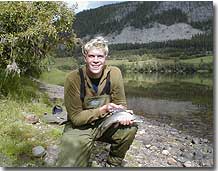

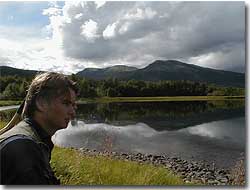

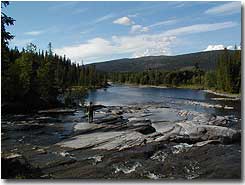

PART I I’m going to leave out the familial bonding which occurred during the six hours we were lost in Paris, France. I’m also going to spare you the agony of a kilometer-by-kilometer account of the 1.6 million meter trip across Germany for some Polish ceramics which are available on the internet with minimal shipping costs (www.polishpotteryshop.com - now you can complete your set, mom!). Because, like me, all you want to read regarding my trip to Europe was how the fishing was in Norway. In one word: Awesome. Day 1: Grayling Stormfront My buddy Einar and I headed out of Sandefjord, Norway at 4:00 a.m. with a plan for two days solid of fast-paced grayling fishing. His cousin’s farm lay on a river that ran cool and clean through the mountains a few hours south of Trondheim, Norway. The small town of Alvdal set the scene as we arrived. After purchasing a week-long fishing license and gawking at the biggest brown trout I had ever seen, mounted above the tackle shop’s cash register, we headed to the banks of the Rolla river. We hopped through a green pasture and watched at the shore’s edge for the circles, indicative of active grayling. “There’s a big one,” Einar would say of the large ripples on the surface of the river. To me, the rises didn’t seem to differ much, but Einar, now 25, had been fishing grayling, trout and salmon on the flyrod for over half of his life, and he could tell you within fifty grams, just how heavy the fish were. He instructed me to tie on his special “grayling fly” consisting of mother-of-pearl wings and white hackle and cast to the nearest rise. My casts were clunky and awkward compared to his smooth crisp snaps which dropped fly after fly in the bullseye-shaped ripples made by the rising fish. However, the grayling did not seem to mind my casts as they rabidly slashed at the pearlescent imitation floating on the surface. After a miss, I set the hook hard on a small grayling, about eight inches long, and stopped for congratulatory high-fives and pictures with my guide. The first fish was in the books, and the second one, hopefully bigger, awaited. I pulled my fly loose from the tree behind me on the next cast, and stepped a few feet deeper into the cold waters which resulted from a combination of springs, meltwater, and mountain runoff. My next few casts, which were markedly improved as the rust fell from my casting arm, were met with explosive rises, but no positive sets. I then placed my fly on a rise located just on the edge of my casting range. SHLURP! The fly disappeared and the line went tight in my hand as I pulled up what slack I had left. “He’s a bigger one,” Einar said from shore, as he removed his net from the back of his flyfishing vest.  The author with his biggest grayling of the trip, a healthy 16-incher caught near the small Norwegian town of Alvdal. The author with his biggest grayling of the trip, a healthy 16-incher caught near the small Norwegian town of Alvdal. The fish ran toward shore, and then back out again, raising its giant dorsal fin to gain leverage against me and the R.L. Winston five weight that was singing in my hands. The drag squealed, as I let this contender go another few rounds. Einar lowered the net to scoop the fish up after two exciting jumps. With a run and a leap the fish bolted between Einar’s legs and the net, and my guide had to play jumprope with the line in order to avoid tripping. The mighty grayling reached for the sky three more times before he settled down. Einar again swooped in with the wood-handled net and landed the fish. This grayling, weighing around 800 grams (nearly two pounds) was impressive. His skin was a dark silver and the fin on his back a brilliant combination of pink, purple and gray. A quick photo and the fish was off. So were we. A change of plans A storm was moving in, and a slight breeze came out of the North. Though the sun still shone, clouds were mounting on the horizon. Einar suggested a quick move to a nearby bend that had proven quite successful in past outings. After grabbing a quick sandwich in the car, we were upstream, watching again for the telltale rises. “There’s monsters everywhere,” Einar said, as he observed the slow moving water of the bend. Indeed, this time there were bigger fish, and even I could tell.  The author's friend and trusty guide, Einar, surveys the river's surface for rises as a storm descends from the mountains in the north. The author's friend and trusty guide, Einar, surveys the river's surface for rises as a storm descends from the mountains in the north. But the wind was mounting and time was running short for good weather grayling. Flyrodding for these fish, (“the only way to catch them” according to my guide, a dry-fly purist) was difficult in windy and cloudy weather. The summer, like the one here in North Dakota, had been similar in Norway. A few quick casts as the wind rose produced a few strikes for me, and one grayling weighing in at a kilogram for the master. Einar smiled for a picture and then frowned as he turned toward the darkening sky. A flock of geese circled overhead, and honked their disapproval at our presence. The fish shut down and the bad weather rolled in. After fifteen minutes of casting blind (as no fish were rising) in the pouring rain and raging wind, we called it good. Einar suggested moving grayling to the last part of the trip, in hopes of better weather, as he figured the trout bite would be on if we headed north to his lake cabin. As we wound our way up the road to his cousin’s cabin in the mountains near Alvdal, I felt the chill in the air, and hoped against the poor weather forecast (which was about all I understood in the Norwegian newspaper) that the next day would bring us better weather, or at least a better bite. PART II In the last part of the Norway Chronicles, despite a few great hours of fishing, an insurmountable northwest wind along with mountain snows had swept both me and my trusty guide Einar off of the grayling rivers of central Norway and up into the mountains of the north. What follows is an account of our arrival at Einar's family farm and our adventures in the mountains nearby in search of trout and char. Out of the freezer, into the mountains As we sped down the last stretch of remote highway near Nordli, Norway, I looked up from the two-degree display on the car thermometer and saw him standing there. "MOOSE," I hollered to my guide, who was off in the hills already casting for trout in his mind. Einar tapped the break, and the young bull looked up at the light green Opel station wagon barrelling toward him. The car decelerated quickly, but not fast enough for my liking, as we stopped just ten yards short of the beast. It was the biggest moose I had ever seen in the flesh, with even, palmate antlers, and about seven points on each side. I pried my fingertips out of the dashboard and snapped a blurry, rain-distorted picture with my camera as he scampered off the road and into the hillside vegetation. "That wasn't even close, and he wasn't even that big," Einar said, detecting a bit of anxiety in my white face and hyperventilation, "I've been way closer than that before," he concluded as he accelerated back up to 130 kilometers an hour. The last twenty minutes of the ride were blessedly uneventful. We pulled into the old Bratteng family farmstead, which lived up to its name, as "bratteng" translates directly from Norwegian into "steep meadow." The backyard was a near vertical green runway into a mountainside filled with trees and shrubs, which I was told, led to highland marshes and then the apex. On the other side of the peak rested angling nirvana. As Einar backed out the "Big Boss" six-wheeler and we loaded the gear, he promised me that the fishing I sought was only a twenty-minute ride away. We hopped on the ATV and headed up the hill. But trout paradise would have to wait. KER-CHUNK! A hot metal line went flying out behind the six-wheeler and the front tires spun two mud strips into the ground. I hopped off and Einar backed the machine to a flat spot. A smoking chain, which connected the back four wheels with the rest of the system, which powered the ATV, was steaming in the rain.  The Bratteng cabin, located on Little Islet Lake, was the base camp for much of the Norwegian fishing adventure. The Bratteng cabin, located on Little Islet Lake, was the base camp for much of the Norwegian fishing adventure. After some convincing, and some re-packing, we stowed what we could under the ATV and packed what we needed in our bags. We would have to go on foot, and it would be an hour walk. I've walked up and down badland hills near Grassy Butte, and made eight-mile days hunting deer and pheasants throughout North Dakota. But by Norwegian standards, I am far from fit, okay, I'm probably far from fit in American standards too. By the time we saw the cabin, silver-gray and well camouflaged with the late summer grasses, the cloudy sky and the chop on the small lake, I didn't care if it was pink with blue polka dots. I needed to rest and catch my breath in the thin mountain air. I watched as Einar bucketed some water from the small creek that ran along the backyard of the cabin and took a sip. "Its so clean you can drink it right here," he said. I'd need more convincing, but in a while I was slurping the crystal clear water down to make up for my jaunt. Cloudberry Lake After a brief rest, Einar warned me that if we wanted dinner we'd have to get it now. So we each grabbed a spinning rod and a couple of copper and red Abu Garcia six-gram spinners and began walking again. By this time I was fully recuperated, and ready for some fishing. We walked into the west, and twenty mile-an-hour winds, toward a small neighboring lake that flowed into the Brattengs' private paradise. We passed little clumps of white and green ground plants, bound into marshy knolls by timeless flows of water and accumulations of ancient plant roots. As we approached the neighboring lake, more and more of these knolls sported little orange beacons. These were multe, or cloudberries, and they looked like neon-orange raspberries, and tasted like no other flavor I had ever experienced. I pegged it somewhere between a combination of oranges and bubble-gum. We stopped every thirty meters to grab a couple fresh berries, now well cooled by the 4-degree-Celsius temperatures. We started casting at the outlet of the small lake, it's shores surrounded by the cloudberry plants. I'd cast and reel in, grab a cloudberry or the occasional wild blueberry and cast again. That was, until my first trout hit.  Student and teacher double up on some great brown trout fishing in some sub-par weather. These browns were caught on bronze/red mepps-style spinners. Student and teacher double up on some great brown trout fishing in some sub-par weather. These browns were caught on bronze/red mepps-style spinners. I reeled in my first brown trout, and smiled for a picture. Einar said the fish looked like a dinner candidate, and I agreed as he slipped it into the creel. Einar would land the next trout, which he named breakfast. As the rain subsided for the night, we began our trek back over the hills, creeks and marshes between what I had dubbed "Cloudberry Lake" and the cabin. We stoked a fire, lit the propane stove, started the kerosene lamps and before I knew it a meal of fried trout, hot bread and potatoes sat before us. "Who needs electricity," I thought, as we raised our glasses, as we toasted 'skoal!' A Whale of a char The next day, the sun didn't even bother to rise over the peaks of the mountains surrounding the vast flat marshlands and lakes. An endless bank of clouds, high winds, and four-degree temperatures kept the sun down, but not us. We ate breakfast and left the cabin early and started off toward the lake to the east. The lake was called Whale Lake, and Einar said there were several areas that held distinct possibilities for good trout and for a chance at char. I hooked a couple of small brown trout on a larger spoon in red and gold, but they were inadvertently released near shore. We were about halfway around the lake when Einar landed the lunch trout. He walked to the back corner of the lake, as I remained facing dead on into the wind, casting the ten-gram spoon straight ahead. The waves broke incessantly near the shore, where the waters rose out of the blue-black abyss and onto the gray rock shallows. As my spoon rose across the rock, so did a missile from the depths. It was a second that has been forever etched in my mind. I paused my retrieve as a dark gray form turned bright red as it slashed and turned at the spoon. I don't know how the human brain processes things, but I felt the whole trip rewind to the point where Einar told me in the car on the way up, 'if you see red, it is a char.'  The author landed this 18-inch arctic char in full spawning color on Whale Lake, a small lake near the Bratteng lake cabin. The fish was hooked on a gold and red spoon. The author landed this 18-inch arctic char in full spawning color on Whale Lake, a small lake near the Bratteng lake cabin. The fish was hooked on a gold and red spoon. "CHAR! CHAR! CHAR! Its a char," I exclaimed as my guide instinctively dropped his fishing rod and pulled the wooden net from his backpack, like a Norwegian samurai unsheathing his weapon. After some words of encouragement, he swept the fiery fish into the net and lifted him high. The cherry red belly beamed through the netting, and the spoon lay dangling beneath the mesh. We celebrated the biggest fish of the day with a quick handshake and a couple of pictures. I watched as the most beautiful fish I had ever seen disappeared back into the dark waters from where he had come. We continued around Whale Lake, knowing we were completely satisfied if we didn't catch another fish. But the trout must have been excited by the battle that echoed through the little lake valley just moments before.  The master lands a chunky brown trout on Cloudberry Lake during a break in the rainstorms. The master lands a chunky brown trout on Cloudberry Lake during a break in the rainstorms. One after another the master and I pulled in brown trout, until Einar caught our seventh trout at the point we had started at. We walked back through the creek valley between his lake and the Whale. In tow were our first fish of the day and the memories of eight more that we had released. As we sat down for yet another trout meal, this time boiled and served with onions, potatoes and wild mushrooms we picked in the woods nearby, I thought about the vastness of the world and how I had ended up where I was at that very moment. I often had thought about a place where all there was to do was fish. And even with the wind and the clouds outside, my imaginary paradise wasn’t as beautiful as the one I was in. I commented on my thoughts to my host and he replied, “You should see it during grouse season,” he replied pointing to a picture of the cabin covered in four meters of snow. Smiling, I stated that it looked a lot like home…just not during our grouse season. PART III In the last part of the Norway Chronicles, Einar and I explored the mountain lakes surrounding his family cabin in the mountains of northern Norway. Despite the wet, windy, and cold weather the action for wild brown trout in the crystal waters was red hot. Calm Waters, Calm Fish After four days of cold front action, the gray skies lifted and broke to reveal clear blue ceilings reflecting down on the mirror-like lakes of the Norwegian mountains. Walking around in the sunshine and stillness of the highlands was like walking through time itself. Mounds of ancient roots held up green and red leaves, with the occasional yellow group of cloudberries or wild blueberries heralding a quick stop for a snack.  The author tries his hand with "the otter" on Little Islet Lake. The author tries his hand with "the otter" on Little Islet Lake. Well-worn creek beds, coming down from the timeless rocks and furrows in the mountainside crossed our path every so often. Each one bubbled with the excitement of the summer day, as the tiny channel moved the rainwater from the last few days toward Little Islet Lake. We began our trek early, taking us around both Cloudberry and Whale Lakes in search of the fast-paced action from the day before. What we were met with were some finicky brown trout, which were much smaller than the quarries from the previous days. Figuring we had educated a good number of the trout in the small mountain lakes, we pressed on in search of active, but less-intelligent fish. ‘Otter’ Ways of Fishing Despite a gorgeous day, the fish were less than cooperative. Einar then suggested going on a search mission for bigger brown trout. We had seen the fish rising on from the shore near his cabin on Little Islet Lake, and in a flash, the master brought out his secret weapon. "We call it ‘the otter’ here in Norway," he stated. The contraption itself was aptly named, as Einar recounted his tales of taking massive brown trout as effectively as the water-loving mammal. The otter was a gigantic planer board, similar to the ones used here in North Dakota for walleye fishing. It paralleled the boat, while being tethered by fifty-kilogram test line to a handle, which was held in the boat by an angling passenger. In between the planer board and the handle were seven various bright-colored streamers. The idea was to attract and trigger aggressive trout with the larger, flashy flies. I stepped carefully into Einar's family rowboat. The vessel was decades old, built by the hands of Einar's grandfather. It had been used by three generations of the Bratteng clan when they visited the cabin throughout the years. It was old and well worn, and despite a small leak near the plug, which required a quick bailing every twenty minutes or so, the boat was in very good shape for its age. The otter ran along side the boat, as Einar paddled, streaking the streamers just under the glassy surface of the lake. There were no bites in the prime areas Einar had pointed out. There were no hits from between the islets that always produced for my guide in the past.  Success! - This brown trout, weighing over one kilogram, came on the middle streamer fly on the otter. Success! - This brown trout, weighing over one kilogram, came on the middle streamer fly on the otter. The sun was high in the sky, the wind was calm, and the trout were wary. As we decided to hang up our ottering gloves, there was an eruption between the handle I held and the planer board. A ‘V’ formed in the line and I nearly lost my grip on the handle. In a great splash, a large brown trout surfaced and dove back, shattering the reflective surface of the lake. I likened it to fighting a pike on a tip-up while ice fishing. There was the same gentle give-and-take of line with the need to control the amount of pressure put on the rough and tumble action of the fish. It was fishing at its very basics, no reel, no drag, just the hands of the angler and the might of the fish. This time the fish, a chunky brown trout weighing well over a kilogram, lost the bout and was held up for a quick memorial picture and released to battle with the otter some other day. That night we didn't dine on trout, but instead on some of the various groceries we brought up from the valley. I was disappointed that I wouldn't have fish again for dinner, but I knew there would be plenty more chances as the end of the week approached. After a quick two-fish walk around Cloudberry Lake, I sipped on a can of beer and watched the sun set from the deck of the cabin, recalling all of the fun memories made in the past few days. "You know, you have a piece of heaven right here," I commented to my host. He replied in the affirmative. "When I die, can I come here?" I asked wistfully, knowing the end of our time at the cabin was drawing near. "Sure, you can even come back before that if you like," he said chuckling. Fishing The Falls We packed our gear, clothing and foodstuffs the next day and headed down the mountain. Einar stopped for one last look at the lake and I took a quick picture to remember our adventure base camp. The late-summer sun shone down on the water, and a slight breeze blew the grasses in rhythmic fashion. Grouse flushed around us on the hillside as we headed back to the Bratteng farmstead. Upon our arrival we stowed the spinning rods and picked up the fly rods once again. My arm felt nearly as rusty as it did on the first leg of the trip near Alvdal, but I was not one to fear a bad cast. We headed to a river, connecting two big lakes in the valley near the small town of Nordli. Slate gray cliffs dropped down into a tiny rapid stream, the only outlet for the massive lake that lay to the north. The descent of the water was rapid, and the water churned in the life-giving oxygen as it approached the falls below. On this river there were two sets of waterfalls, each different, yet both amazing in their aesthetics. The upper falls, a powerful chute-like set of rocks, produced a foamy flow leading out into two deep pools. And in the serene pools, wild brown trout surfaced constantly on small white and brown insects hatching and swirling in the evening air. Rises dimpled the surface every minute, and the action was sure to be intense. A stepping-stone path led out from the shoreline, giving a novice like myself the chance to cast, even if it was sloppily, at some rising trout. Einar stuck with me until my cast began to come back, and waited until a rise came on my brown parachute hatcher. I set the hook and battled in a nice brown trout, perfect for dinner. The master then set to work ading stomach-deep on mossy rocks across the flow. When in place he methodically began placing thirty-yard casts on saucer-sized ripples, and eliciting strikes from nearly every rise that he saw, and landing every third fish that hit. His back cast curled like the bend in a paperclip, smooth and symmetrical. On the other hand, mine managed to clip the lone tree behind me several times before I got it straightened out. By the time the sun was setting, I was on track.  Einar makes his way down the stair-step cascade of the lower falls on the river near his family farmstead. Einar makes his way down the stair-step cascade of the lower falls on the river near his family farmstead. We headed back onto the mossy path in the woods, and followed it down to a ridge overlooking the falls. We watched as fish everywhere rose and dined on tiny insects. Moving along, we stepped our way down the dry pink and grey slabs of rock which appeared to come out of the mossy edges of the lower falls. The water levels were low, as was normal for late August in the area. This provided us with a single outflow of water in the lower falls, and two distinct areas to work on either side of the flow. I saw a fish rise just off to my left and told my mentor, "I'm going to get this one." The cast laid out crisp and smooth and soon a quick ripple under my hatcher tightened the yellow line. A small brown trout came to hand, as Einar applauded my sight-to-release skills. "That was a work of art," he complemented. I smiled and thanked him, telling him that the credit was all his. We probed the pools and shorelines around the lower falls, but found they were not as productive as the two pools above. We headed back up through the woods toward the upper falls, and arrived as the sun was setting over the tall alpine forest. It was like another world of fishing to be in the middle of that setting.  Water rushes down the chute-like rapids of the upper falls into the pools, teeming with hungry trout. Water rushes down the chute-like rapids of the upper falls into the pools, teeming with hungry trout. That evening we fished until we could barely see the rises, casting only to the small slurping sounds we heard beneath the noise of the falls. We competed with the trout, while they in turn competed with a few bats looking for a sonar-detected snack as evening turned to night. The trout quit rising, or at least we quit hearing them do so, and we called it a day. We packed our gear and headed back to the farmstead for yet another tasty dinner of trout, mushrooms and potatoes. We saluted the good fishing and prepared for the long drive down, and the last three days of our trip back to Oslo for my flight out. I would take many memories back to the States as souvenirs of my trip with a good friend and good fishing found so far away, yet still a part of…our outdoors.

|