Fly Fishing with Doug Macnair: Folk Tales and Fly Rods: Part 3©

Fly Fishing with Doug Macnair: Folk Tales and Fly Rods: Part 3©

From his manuscript, Fly Fishing for the Rest of Us

Considering all that has been covered thus far in the discussion of folk tales and fly rods, the time has come to tackle the thorny subject of selecting a specific rod. Before going further, however, please accept my counsel: (1) If you are already into fly fishing, do not let the selection process become biased or emotional; (2) If you are just getting into the sport, do not allow yourself to become adversely influenced by others. Instead, be guided by what I said earlier about objectivity in rod selection.

- The rod is in the right line weight range for the size of the fish you intend to pursue.

- The rod length is suited to the water(s) and environment where you plan to cast your line(s).

- The cost of the rod is sufficient to make it "something of value" and, therefore, worthy of your tender loving care.

Up front, understand that almost any fly rod will cast up or down at least one line weight from the rating specified by the manufacturer. As an example, a 5-weight fly rod is capable of casting either a 4-weight or a 6-weight line. However, the "when" of using these alternatives must await the discussion of the fly cast. So what does it mean when a manufacturer "dual" rates a rod 5/6 or 7/8? Using the 5/6 as an example, the dual rating usually means the rod does best with a 5-weight double-taper (DT-5F) line or a 6-weight (WF-6F) line. At least one manufacturer rates their rods suggesting the lighter weight for distance and the heavier weight for close-in work. For now, the point to be made is simply this: most fly rods can and will cast more than one line weight.

By now, you should know that the term, "rod weight," has nothing to do with the actual weight of the rod. Instead, it refers to the line weight the rod casts. Remember, it is the line that loads the rod enabling the cast, not the weight of the lure as in baitcasting or spinning. The working relationship between line and rod is critical to the efficiency of the fly fishing system. When rod and line work together, it is likely to make for a lovely day; however, rod and line begin to work against each other, the day can quickly turn into a loser. If the line aerialized is insufficient in weight to load the rod - in other words, forcing the rod to bend thereby storing the energy necessary to make the cast - the cast cannot be made. On the other hand, overloading the rod with too much weight can cause the rod to collapse. This is a nice way of describing what otherwise is apt to be an explosion, leaving the fly fisher with little but shards of graphite.

A Quick Review of the AFTMA Standards. How do you weigh and classify a fly line? In "All About Lines," I explained line weight refers to the number of grains contained in the first thirty feet as defined by the AFTMA standards. (SEE: All About Lines, Part 1.) To get a rough approximation of the actual weight in grains, I suggest multiplying 30 as in thirty feet, by the AFTMA line weight classification. Using a 4-weight line as an example, expect the first thirty feet to weigh roughly 120 grains. Important? You bet!

The issue of line weight involves subtleties many fly fishers do not understand. Under the AFTMA standards, the magic number "30" really means that the first 30 feet of 4-weight line will load a 4-weight rod. It follows that under the standards, the first 30-feet of 5-weight line will load a 5-weight rod. The constant is the number 30. Simple? Hardly! Like everything else, the AFTMA standards actually apply over a weight range of ten or more grains for each line weight. Of course, all the line beyond the first thirty feet also has weight; how much more depends on the specifics of the design of the belly and running sections.

What many folks fail to realize is that as the line aerialized is greater than 30-feet, how little it takes to artificially increase the line weight equivalent. As an example, raising 4-weight line to a 5-weight equivalent only requires a little over five feet of additional line. Thus, lifting thirty-five feet of 4-weight line into the backcast is about the weight equivalent of a 5-weight. Five extra feet doesn’t seem like much, but it can be. An additional five feet here and there can add up to rod overload as your casting proficiency grows, especially if you begin to shoot line to the rear on the backcast. Suppose using the double-haul, you’ve got forty-five feet of line hanging in the air as you begin the forward cast ... Ever wonder how much weight you are asking your little rod to throw? I think understanding line weight is very important.

In fly fishing, only line weights are standardized. Everything else - including the weight ratings to fly rods by the manufacturers - is subjective. Consequently, rod ratings are imprecise and in the eyes of the beholder. Despite the potential for human error, rod ratings provide a convenient way to begin your search for the perfect weapon to use against friend fish. Remember, I suggested earlier that selecting a fly rod is a lot like selecting a car. Do not make the mistake (as I have done) of becoming enamored with the wrong rod. A wise man would likely not consider a lovely little 3-weight as the rod of choice for (1) enticing the strike of a largemouth bass, or (2) chasing a trophy red in the saltwater flats. To be sure, you can use a 3-weight, but I am willing to bet you will be buying another shortly after you set the hook the first, second or third time. If, however, you are one of the few who can achieve success with ultralight fly rods on big fish, please admit you are not into catch and release. Tiring a fish beyond its capacity to recover kills the fish.

The Actual Weight of the Rod. Quite often, deciding on a specific rod can get tough when only two or three candidates remain in contention. Should this happen, I suggest factoring in the actual weight of each rod. Generally, a 7-weight weighs a little less than a comparable 8- or 9-weight by the same manufacturer. The 1997 Orvis catalog, for example, lists the Power Matrix-10 907 9-foot, 7-weight at 4 3/8 ounces; conversely, the Power Matrix-10 909 9-foot, 9-weight, lists at 5 1/8 ounces. Now, that doesn’t sound like a big difference, and it isn’t. However, look at the reels Orvis recommends for both rods: for the 907 it is the DXR 7/8 at 6 5/8 ounces and for the 909, the DXR 9/10 at 7 3/4 ounces. The difference between the two outfits is now almost two ounces. The DXR 9/10 is a bigger reel and, therefore, carries the heavier fly line and considerably more backing. When you add the weight of the backing and line to both outfits, you’ve frosted the cake: Rigged and ready to fish, the 9-weight will weigh between three to four ounces more than the 7-weight. My friends, this is a weight difference that can adversely affect casting performance over the stretch of a long day on the water. Do not over-rod yourself.

In the foregoing example, the increased backing capacity of the DXR 9/10 over the DXR 7/8 refers to traditional backing, not the micro-fiber lines. In fishing big waters for big fish, I do not believe it is a good idea for a fly fisher to sally forth for battle without 150 to 200 yards of backing. Some might argue even more backing is required, and against the right fish in the right water, they could be correct. When "bigger is better," the logic goes something like this: (1) bigger fish require a bigger reel; because (2) a bigger reel has a bigger spool; and (3) a bigger spool will hold more backing, as measured in yards, test-weight or both. To properly balance in the hand of a fly fisher, the bigger reel requires a bigger rod.

The advent of the micro-fiber backing materials, such as Cortland’s Micronite, changed the picture. Load the DXR 7/8 with Micronite and its capability and capacity goes up dramatically. I believe saving weight in the fly fishing system - rod, reel, line and backing - is important to making an enjoyable sport even more enjoyable. My experience with micro-fiber backing suggests the reel can be reduced at least one size while holding backing test weight and yardage constant. When you can drop down one reel size, you save weight and money. Small reels cost less than their bigger brethren. There are those, of course, who argue against the micro-fiber lines. If not spooled very tightly, it is possible for the line to dig into itself when it meets the pressure exerted by a fighting fish. In my view, too much has been made of this argument. Any backing, micro-fiber or traditional, will snarl if not spooled tightly. The solution the problem is obvious: always tightly spool the backing.

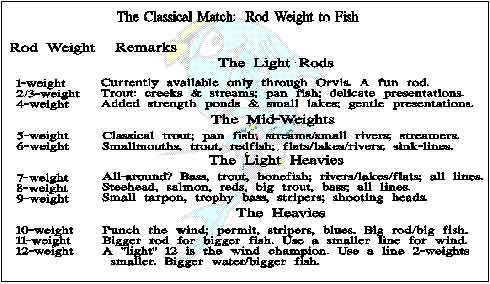

To assist in the rod selection process, review my classical match of rod and line weight to fish and water. (SEE: Classical Match.) Just remember, nothing is precise in this guide except as it applies to the wind. If wind is a constant problem in your fishing environment, equip yourself to fight the wind more than the fish. The point should be obvious: when the wind prevents you from getting the fly to the fish, don’t expect to very many fish. Wind fighting requires the right tools. More on this later.

Which is Best: A Two, Three or Four Piece Rod? Not so very long ago, 3- and 4-piece sectional rods were not held in high favor by seasoned fly fishers. These so-called "travel" rods simply did not cast as well as their 2-piece counterparts. Now however, the travelers are almost as good as the 2-piece variety. Instead of being shunned, the 3 or 4-piece rods have become the rods of choice. No doubt about it, it's convenient to break a long rods into smaller segments. For example, an Orvis Powerhouse 2-piece measures 56 inches resting in its tube while the Powerhouse Traveler measures a short 29 inches. Which would you prefer to toss into the car, carry along on an airplane, or ship by overnight mail?

Of course, there is also a minor thing called "price" to throw into your decision. Travel rods now cost substantially more than their 2-piece kin. Returning to the example of the Powerhouse, the 2-piece version lists for $410.00 while the travel version runs a cool $475.00. There are lots of folks like me who stop and think about the value of an extra 65 bucks; after all, the first $410.00 comes hard enough. If you don’t plan to visit Timbuktu by canoe, the 2-piece is a good choice. I prefer the 2-piece to all others, provided I don’t have to wrestle with it when traveling by commercial carrier. The fact is I have yet to cast a 4-piece rod that casts as well as its 2-piece brother regardless of the manufacturer’s claim.

Up or Down, That is the Question. Another feature worth considering is the reel seat. There are two kinds, uplocking and, yes - you guess it - downlocking. Both styles are tried and proven and have been in use for years. Given a choice, I suppose I favor the uplocking seat. Doing a long stint of fishing, the movement of the casting hand can loosen the adjusting ring on a downlocking seat. Having a reel fall off the rod while fighting the fish will be a laughing matter to everyone witnessing the event. However, if you lose the reel deliberately to entertain your friends, credit yourself with the "X-Stream Humor" award. I also do not favor the downlocking seat for the heavier weights. If you want to pull the rod back into your tummy while fighting a heavy fish, the uplocking seat is for you. The uplocking seat is natural for a fighting butt. On the other side of the coin, the uplocking seat may add a bit to the cost. Remember, for every pro there is usually a con. The downlocking seat has plenty of advocates. Try it; you might like it, especially on a lighter weight rod.

The Long and the Short of It. The question of length always comes up in a discussion about fly rods as it properly should. If the rod is to function as a long lever assisting the fly fisher in making the cast, just how long should the lever be? Length must become a consideration. In truth, either a long or short rod can help or hinder the cast depending on the circumstances. Start looking through catalogs and you are sure to find rods ranging from 6_ feet to 10_ feet in length. On the long end, a 6- or 7-weight 10 to 10_ is a delight when you are floating in water up to your armpits around suspended by a float tube. Since you are so close to the water, the extra length extends the lever’s length, in turn, giving an extra boost when lifting the line from the water into the backcast. On the short end, I assure you a little 6_ foot lightweight is a delight in close cramped quarters where making any cast can be difficult. Try fishing a tight brushy narrow stream with a long rod and you will soon perfect your mastery of four-letter words while reducing the number of flies in the old fly box.

With this background, let me set forth my views on the relative merits of long and short rods. While the long and the short of it have been argued for years, the 1990s began what might be called the "Day of the 9-footer." I think too many folks have come to believe not much can be done in fly fishing with a short rod. That is simply not true! Let me correct your thinking. Lee Wulff, staunch champion of the short rod, proved conclusively, in at least his very capable hands, a long rod offered no advantage. And he did what he did against a formidable adversary in a frequently adverse environment -- fly fishing for Atlantic salmon in the coastal waters of northeastern Canada and the United States. With his little rods, usually less than seven feet, and light lines of 6- and 7-weight, Lee consistently cast between 80 and 83 feet. I find this very interesting, don't you?

In picking a rod length, I hope it is because it "feels right," not because some store clerk (sometimes called a fly fishing expert) sings its praises. A rod that feels right is apt to be right, especially when it comes down to the slight differences between 8, 8_, and 9 feet. If the 8 feels better than 9, buy the 8. Make your choice based on rational thought with only a tad of the heart at play, not the other way around. I will let you in on a little secret: Very much like Lee Wulff, I, too, love those little short rods. There is something about the little wands that excites me. Pressing a 6_ footer to the limits of its capacity or mine, as the case may be, is just plain fun. If you not yet made up your mind, study the chart. It depicts a few factual advantages and disadvantages between the two.

The Long and Short of it

Short Rods

Advantages

- Ease of transport: A more expensive travel version is not required

- Maneuverable: Easy to cast in confined areas - trees, brush, small streams.

- Lighter in Weight: Short rods weigh less than long rods of the same weight.

- Fun--A Challenge: Not forgiving of casting errors. Requires best effort.

- Fast: Develops high line speed easily; throws a tight loop.

Disadvantages

- Mending Line: Comparatively speaking - difficult.

- Hard Work: It takes more effort to be efficient.

- Short Lever: Increases the difficulty of lifting the line into the backcast.

Long Rods

Advantages

- High Backcast: Enables a higher backcast with comparative ease.

- Long Lever: Comparative ease in lifting line from the water.

- Mending Made Easy: When mendng line is critical, do it with ease.

- Casting Error: Long rods are much more forgiving of mistakes.

Disadvantages

- Weight: Length adds weight.

- Awkward and Clumsy: Easy to tangle in close quarters.

- Casts a Wider Loop: Don't kid yourself, the short rod has advantages

- Advantage Fish: In the landing zone, it's advantage fish.

In the end, the choice between the "long and the short of it" is up to you and a thing called "individual preference." Begin your search only after you’ve given the subject a lot of thought. A final thought on rod length: practicing the fly cast in an urban environment is easier with a shorter rod. Like it or not, practicing the cast is a requisite to becoming a competent fly fisher. (It is also a great way to relieve stress.) Beyond these words, I have no magic dust to help you make the "best" choice. It is hard to far astray by selecting a rod between 8 and 8_ feet. If you plan to fish only open lakes, rivers and the saltwater flats, try a rod 9 feet in length.

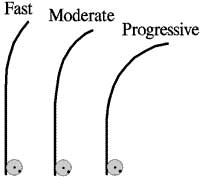

Which Action, Jackson? The action of the rod is something of concern during the selection process. As you learned earlier, the variables the rod manufacturer controls include the taper or diameter, the wall thickness, and the graphite materials. Rod engineering between manufacturers has resulted in an array of rod actions, at least in name. Be advised, however, that two "fast" rods from different manufacturers are not likely to have the same action, although the weight and length may be the same. Reduced to its simplest terms, there are really only three-rod actions: progressive, moderate, and fast. (SEE Rod Actions.)

- A rod with a progressive action is "softer" than its counterparts, having more flex or bend throughout its length. Considered by many as an "old action," it nevertheless remains a favorite of many veteran fly fishers for very prudent reasons. If a soft, precise and accurate cast is required over a short to medium distance, I know of no better choice. Besides, the progressive action is the most forgiving of the lot to a casting error. Screw up the cast and you will still be playing in the ballpark. Make the same mistake with a fast-tip, and the result will send you to the dugout to repair your snarls and wind knots. One other point: no other action protects a light tippet during the strike like the progressive action. If "feel" is important in fly fishing, no other rod gives a better "feel." Believe me, there are plenty of times when fly fishing is all about "feel."

-

A fast action or fast-tip rod is the opposite extreme of the three actions. The tip does most of the initial work with the rest of the rod responding and flexing only on demand. If all you ever intend is fly fishing saltwater for any number of tough gamefish, this is the action for you. At distance, the fast action is inaccurate. Then, too, it is the most difficult action to master. While it is not forgiving of casting mistakes, the fast-tip rod throws a very tight loop a very long way, even in the face of adversity. Adversity in fishing the salt is something I call "the wind." On occasion, many fly fishers have come to refer to the wind by other four letter words.

A fast action or fast-tip rod is the opposite extreme of the three actions. The tip does most of the initial work with the rest of the rod responding and flexing only on demand. If all you ever intend is fly fishing saltwater for any number of tough gamefish, this is the action for you. At distance, the fast action is inaccurate. Then, too, it is the most difficult action to master. While it is not forgiving of casting mistakes, the fast-tip rod throws a very tight loop a very long way, even in the face of adversity. Adversity in fishing the salt is something I call "the wind." On occasion, many fly fishers have come to refer to the wind by other four letter words.

- The moderate action is somewhere between the fast and progressive actions. Like anything in the middle, it does not represent either extreme. The moderate action is very popular with many fly fishers. In several instances, the manufacturer’s advertising spin suggests the rod is fast, capable of developing high line speed(s). That is not entirely true but it is not entirely a lie. It all depends on how one defines "fast." After all, if "fast" means faster than "slow," then "fast" is fast isn’t it? Many of the "fast" rods advertised today take their roots from the moderate action. Try it, you may like it. It is forgiving of casting errors and fully capable of making gentle presentations. Pick one up and wave it in the air, preferably with the reel of choice mounted and some fly line dangling from the tip. If it feels right, it probably is, at least for the time being. The moderate action is sort of like a glass filled half with water and half with air. Depending on your frame of reference the glass is either half full or half empty. Know that most of our long rods fall into the moderate action category.

The Grip. On the lighter weight rods, say from the 1-weight through 5-weight, whatever grip feels right is right. But on rods 6-weight and above, I suggest you consider the full-wells grip. The slightly raised forward edge pushes back at the pressure of your thumb giving you better control over the rod during the cast, especially after several hours on the water.

The Reel Seat. There are some beautiful reel seats made of lovely woods such as curly maple, birds-eye maple, cherry, walnut, and a number of very costly exotics. Add some nickel-silver hardware and, as they say down here in Texas, you’ve got yourself something real pretty. For harsh environments and tough conditions, do yourself a favor and get something practical like anodized aluminum. A couple of years down the road, you will look in the mirror and wonder how you became so smart.

A Word about Warranties. Almost all manufacturers now offer a lifetime warranty on their rods. Credit Redington for having gotten the "lifetime warranty" ball rolling down hill for us users. Unfortunately there are those who are likely to screw-up our good fortune. These are the same folks I spoke of who are not into taking care of anything, especially a fly rod under warranty. Some use their rods and "put them away wet," as a horse soldier might say. With no maintenance, wear and tear sets. At this point, these fine upstanding Americans break the rod, lie to the manufacturer about the cause, and demand a replacement. The truth is the manufacturer can tell immediately whether the break occurred from a manufacturing failure or through either a deliberate act or act of stupidity. For those of you who fall into the former category, you have my condemnation; for those of you who may simply be accident prone, I offer the following from my own experience.

Always remember to use care when and where you assemble or disassemble your rod. Whether long or short, it is awfully easy to run into things with a rod, especially in your home. The spirits of the ancient Fish Gods await there in the shadows for the chance to take revenge. Without your abiding attention, you will learn car doors and big feet are evil things. Given the slightest neglect on your part, the ceiling fan will hum and turn with joy after eating the tip of your new rod. Then, too, beware of the motions and movements of the vacuum cleaner. They are sneaky, but quick. I know them to be dirty degenerate machines just awaiting the opportunity to take you to the cleaners. I watched in horror as my vacuum - without conscience, reflection or regret - slowly sucked the very life from a slender 6_ foot bamboo rod, and having taken its fill, tossed the splintered body aside. Grown men cry. I cried. Make the same mistake and you will cry, too. (From Fly Fishing Texas © Copyright: Douglas G. Macnair, 1996.)

If you think my comments harsh, know this: you and I are the ones who pay for the rods broken by deliberate abuse or stupidity. The manufacturers have no alternative but to raise the retail price of their fly rods, thereby passing the cost to us. Frankly, I am tire of paying the way for others. Unless you have unlimited funds and live on Mount Olympus with Zeus and the other gods, I'll bet you tire, too.

Summary. Now it is time for the game called, "If I were you..." If new to the sport, begin your experience with a slower action rod. The progressive action will help you in developing your skills while providing all the distance necessary to catching friend fish. Most males cannot go wrong in selecting a rod 8 to 9 feet in length. A female, on the other hand, might prefer a rod 8 feet in length. Once the rod is in on hand, reach for it anytime you want a few moments to relieve stress. A few casts on the grass will do it every time. Practice is as important to mastering the fly cast as it is in mastering the golf swing. Closely cut grass will not damage your fly line. The best part, however, you do not pay a green fee for the use of the grass. Carts, of course, are not required.

Selecting a fly rod can be fun, if you make the search an adventure. Most do not. They enter the nearest fly shop and within minutes make their purchase. Buyers beware -- do not fall for the old gimmick of buying what the fly shop wants to sell you. The gag goes something like this: "The (fill in the name of the company) builds beautiful rods, but it is a very small firm. Right now, they are way behind production. It will take months before we can fill your order. Let me show you this rod built by (fill in the name of the company) that is at least as good, if not better. In fact, it is the rod of choice by knowledgeable fly fishers who really know the sport."

For those of you still at a loss as to what to buy, try these final guidelines. If you decide on a shorter rod, do not get one less than 7 feet. If your shorter rod is for small trout or pan fish, buy a 3- or 4-weight. If your mid-length (8 feet) is for trout and pan fish on larger streams and ponds, try a 4- or 5-weight. If your longer rod (8_ feet) is for bigger trout, pan fish and smallmouth bass in rivers and ponds, try a 5- or 6-weight. If your long rod (9 to 9_ feet) is for broad rivers, lakes and/or the saltwater flats go for a 7-, 8-, or 9-weight. Now, "The moving hand having writ what it is I knowed to write, I conclude this here piece done, nowhow anyway." Good luck!

Next up: The discussion moves to "Real Reels: Fact and Fantasy." Hope you decide to stay tuned in. It should prove an interesting time in this series. God Bless.

© Copyright: Douglas G. Macnair, 1997-2001.

|