Economizing Scope and Improving Results

Economizing Scope and Improving Results

By Noel Vick

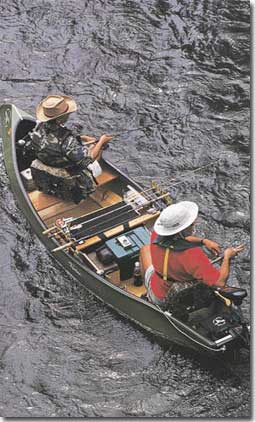

Bill Plantan, an impassioned river buff, often speaks about this guy who owned a big boat – the fast and glass sort – and nearly exclusively launched it on big water. One day, for whatever reason, he bought a canoe, a River Ridge Custom Canoe, and thus began a new chapter in his fishing career. As it turns out, that chapter evolved into a book, because once he learned how to fish moving water, well, that big boat never saw big water again.

“He mailed me a letter the other day,” Plantan said enthusiastically. “In it, he talked about a December 1st float on the Upper Mississippi River where he and a partner caught 40 smallies, including a 20 incher.”

In fishing, that’s an epiphany.

Plantan’s own fishing-methodology has evolved to where he only fishes lakes that are petite and tricky to access, and water that surges across the landscape, namely rivers and streams.

“Moving waters are my foremost targets – big and small ones. I’ll put a canoe in anything with current,” said Plantan, laying out a template for ‘his kind of fishing.’

The reasons for electing waters with current are manifold. In no particular order of significance, Plantan first points to the reduced boat traffic. Rivers and streams attract fewer boaters, period.

And then there’s the weather thing. Current dwelling fishes are less affected by atmospheric shifts. Swings in barometric pressure greatly influence activity in lake-going fish, but for the most part, that’s not the case in current. Although, according to Plantan, incoming spates of low pressure trigger feasting-scenarios faster on rivers than lakes, albeit for shorter durations.

“On rivers, baitfish will physically rise on the front side of a storm or other low pressure event, and that really turns the fish on, especially trout, and sometimes smallmouth bass,” Plantan said.

Wind is yet another factor. The comparatively narrow and elevated banks on rivers and streams buffer winds and yield fishing opportunities even when nearby lakes are too rough to navigate.

Multiplicity is a frequent upside of moving water too. Few fishing trips are relegated to a single species. Walleyes often intermingle with northern pike, sometimes catfish, and brutish smallmouth bass have no qualms about sharing a pool with a muskie. Even designated trout waters surrender bonus catches.

Finally, there’s the availability factor. Most folks, no matter their place of residence, can peruse a map and find a navigable stretch of moving water within an hour of home. That claim can’t always be made for lakes, though. And in regions where lakes dominate the landscape, rivers and streams often trickle in virtual obscurity.

By now, Plantan should have you salivating at the idea of drifting and casting a serene and scenic waterway. Maybe you’re even thinking about ditching the 20-foot warship for a humble canoe. But fortunately, canoes are relatively inexpensive, so you shouldn’t have to sell the cruiser to own one.

By now, Plantan should have you salivating at the idea of drifting and casting a serene and scenic waterway. Maybe you’re even thinking about ditching the 20-foot warship for a humble canoe. But fortunately, canoes are relatively inexpensive, so you shouldn’t have to sell the cruiser to own one.

So with intentions to float and fish, the next step is selecting a flowage or suitable stretch of a major system. “First off,” says Plantan “you need to know the ‘gradient’ of the river or stream in question.”

Are there rapids? Is the current swift or lazy? Answers to questions like these will determine if the tract of water is hazardous to pilot, possibly dangerous, or simply too taxing navigationally for an afternoon of fishing.

(The website TopoZone.com (www.topozone.com) is a phenomenal resource for mapping rivers and streams of interest, as well as investigating your area for prospective moving water.)

The topic of gradients feathers into Plantan’s next consideration which is ‘float time’: how long it takes to travel from point A to point B.

“I usually figure about a mile an hour, so an eight mile stretch would take approximately eight hours to float. If you’re just canoeing, it’ll go faster, but that’s a pretty fair average when you build in fishing time.

And if there’s any doubt, err to the safe side. Don’t bite off too much water. Getting caught in the dark on unfamiliar water can be precarious.”

Plantan also suggests that canoeists plan for pickups and dropoffs well in advance. He likes the two-vehicle program, where a second vehicle is planted – no pun intended – downstream, at the concluding point. Afterward, the anglers, motoring with canoe overhead, drive upstream to the originating point and launch. Where available, canoe rental outfits provide similar services. Such establishments are prime sources of river information as well.

Locating a navigable sliver of current is child’s play. As Plantan asserts, “they’re everywhere.” But his screening process cuts deeper, earmarking certain types of waters under certain conditions.

“Most people automatically think the decision to float one river over another is dictated by preference of species. I prefer to let prevailing conditions guide me, not a particular species.

I have a ball catching just about anything.”

Plantan says the best overall waterway to explore, regardless of species, unfolds below a dam. Fish of all makes and models gravitate toward the supplementary depths, current breaks, and wealth of food that dams provide.

“Fishing below a dam can be really productive after a rainfall. The water upstream turns swift and cloudy right away, but it takes awhile for the runoff to influence clarity and current speed downstream, below a dam,” Plantan says.

The inverse applies to the days following a rain event. “It takes two to four days, on average, for a river to clear-out after a rainstorm. And once it does, the upper reaches can really get hot while the lower stretches darken and the fishing slows.”

Time of year is another determinant in the selection process. In the spring, Plantan favors fertile, darker-water flows, the sorts flanked by farmland and pastoral shorelines. From a fishing standpoint, they’re the first to spark. By midsummer, he’s off searching for clearer and deeper runs – ones with limited vegetation too. Here, banks are typically studded with pines and fortified with rock.

By autumn, Plantan fixes on rivers with deep pools. Fish begin congregating in pools once water temperatures approach the 60 degree mark. They frequently remain in those slumbering areas all winter too.

Ultimately, what beckons Plantan to current is the bite. It’s nearly bulletproof. Something’s happening on some river or stream regardless of the weather or page on the calendar. And in his opinion, and mine for that matter, there’s no finer way to fish and experience moving water than from a canoe.

Editor’s note: River Ridge Custom Canoes are available factory direct. To find out more about the utmost fishing-canoe, call (507) 288-2750 and ask for a free brochure. You can also learn more about the company and their products by visiting www.riverridgecustomcanoes.com

|